de Cannes

Over its different editions, the Festival de Cannes has become one of the mirrors of worldwide film production. A number of film movements have been revealed, expressed and affirmed there. Discover 7 major periods that have punctuated the history of the Festival.

“ To a certain extent, everything is realist. There is no border between the imaginary and the real. ”

Federico Fellini

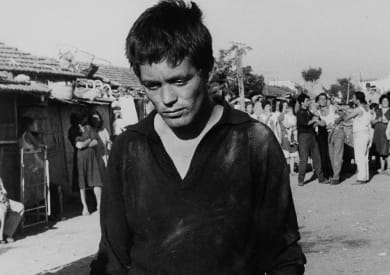

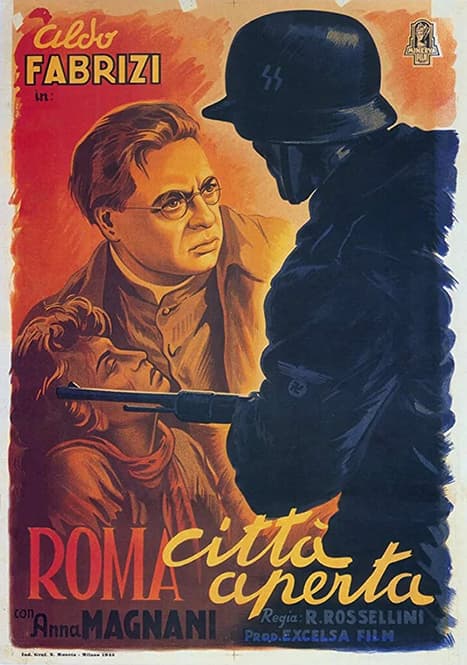

Roma città aperta

Rome, Open City

Roberto Rossellini

This film marks the birth of Italian neorealism. The feature film was selected In

Competition for the 1st edition of the Festival de Cannes, which screened 44 films from

19 countries.

Rome,

Open City won the Grand Prix (the ancestor of the Palme

d’or) alongside ten other films. For the screenplay, Rossellini partnered with Sergio

Amidei – the beginning of a long collaboration between the two men – as well as Federico

Fellini, then a young journalist.

Source: Cinémathèque

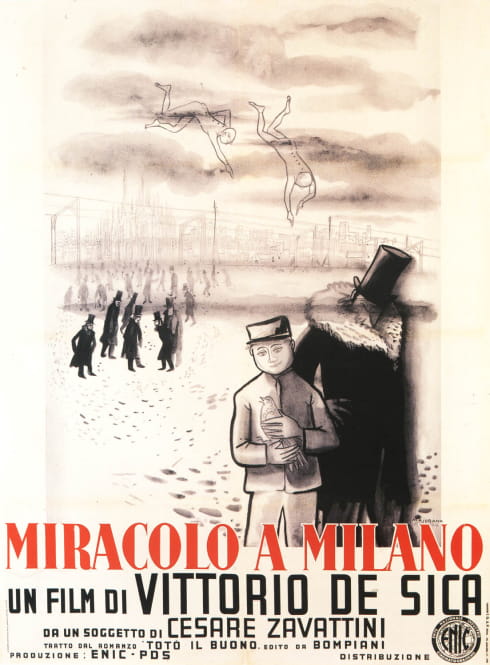

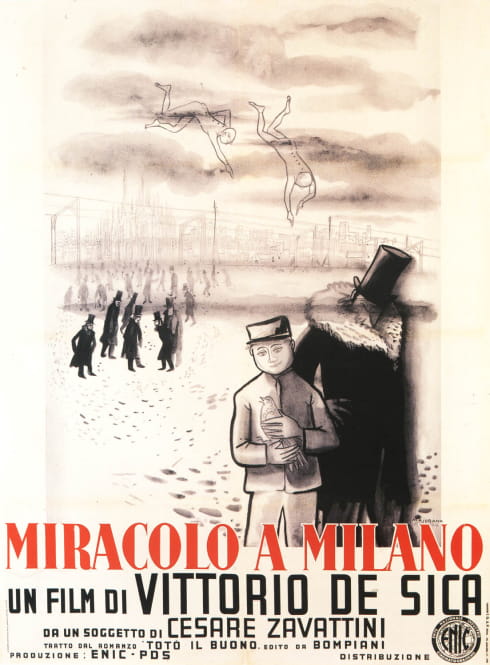

Miracolo a Milano

Miracle in Milan

Vittorio de Sica

A founding member of Italian neorealism, the director of The Bicycle Thieves broke with the rules he had himself laid down with his new film Miracle in Milan. Although the starting point is the reality of a destitute existence, the film progressively moves away from that to take on the allures of a tale, with the appearance of the marvellous. Present in the Official Selection of the 4th edition of the Festival, the film won the Grand Prix, along with Alf Sjöberg’s Miss Julie.

Source: CNC

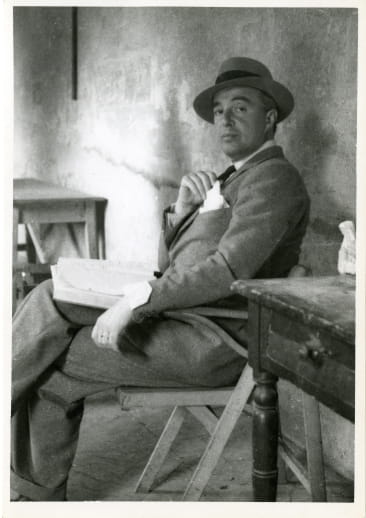

La Dolce Vita

Federico Fellini

La Dolce Vita

Federico Fellini

UA year after’s Les Quatre Cents Coups de François Truffaut, La

Dolce

Vita marked the definitive entry of cinema into modernity.

Upon its release, it left nobody indifferent and soon became a scandal. Fellini’s work

was condemned by the Vatican for its decadent vision of Roman high society. It was even

debated in the Italian Parliament!

But the controversy also led to success: there

were lines in front of theatres and the Jury of the 13th edition of the Festival de

Cannes unanimously granted it the Palme d’or. That same year, another

major Italian film took home the Jury Prize: Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura.

Sources: L’Humanité, La Croix

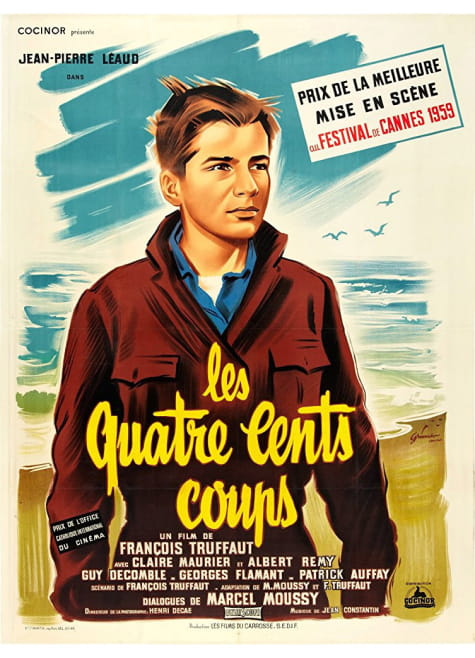

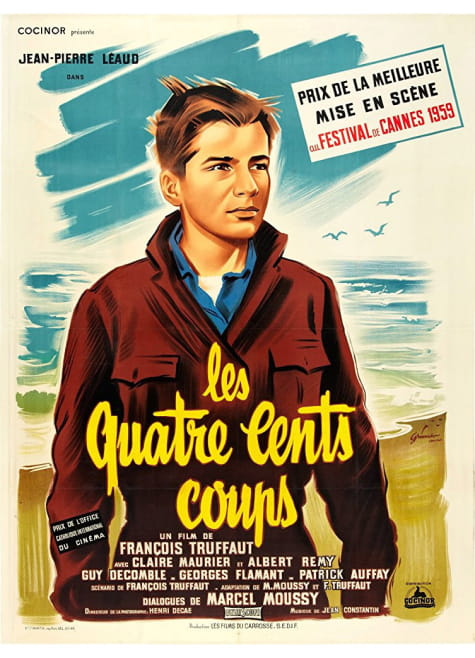

Les Quatre Cents Coups

The 400 Blows

François Truffaut

1959, a historic year? In any event, it was the year that François Truffaut presented

his first feature film at Cannes. It was an immediate success: the story of the young

Antoine Doinel had a triumphant reception at the Festival. At the end of the screening,

the film’s 14-year-old leading actor, Jean-Pierre Léaud, was carried aloft.

While

The 400 Blows did not win the Palme

d’or – that honour going to Marcel Camus’ Orfeu

Negro the film that the New was the Best Director

Award.

Source: Le Monde (archives)

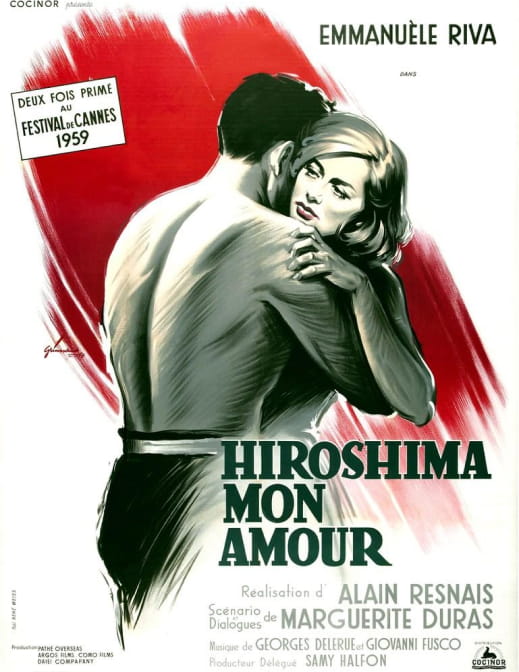

Hiroshima mon amour

Alain Resnais

Released the same year as The 400 Blows, this adaptation of Marguerite Duras’ book was the talk of the town. And for good reason: the film was perceived as anti-American by the US, to such an extent that their delegation asked that it be removed from Competition at the festival. The film was nonetheless screened during the 12th edition of the Festival, but did not compete for the Palme d’or. At the helms of the new Ministry of Culture, the writer André Malraux is said to have declared after viewing the film that Hiroshima Mon Amour was the most beautiful film he had ever seen.

La Religieuse

The Nun

Jacques Rivette

The big-screen adaptation of Denis Diderot’s novel caused a scandal before it was even released. Although twice approved by the censorship board, the film ended up being banned in 1966 by the Minister of Information. An uproar! Numerous artists rallied to support Jacques Rivette – Jean-Luc Godard chief among them. The Nun was eventually selected In Competition for the 19th edition of the Festival de Cannes under another name: Suzanne Simonin, la Religieuse de Diderot. Censorship of the film ended one year later and the film could finally be released to theatres… for those who were 18 or older.

This change valued a more engaged cinema, notably from Hollywood, where a number of new talents were emerging. Among them: Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg.

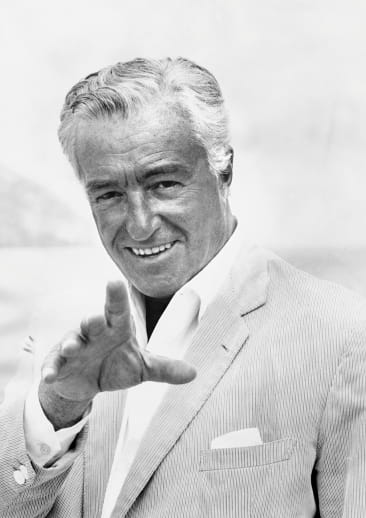

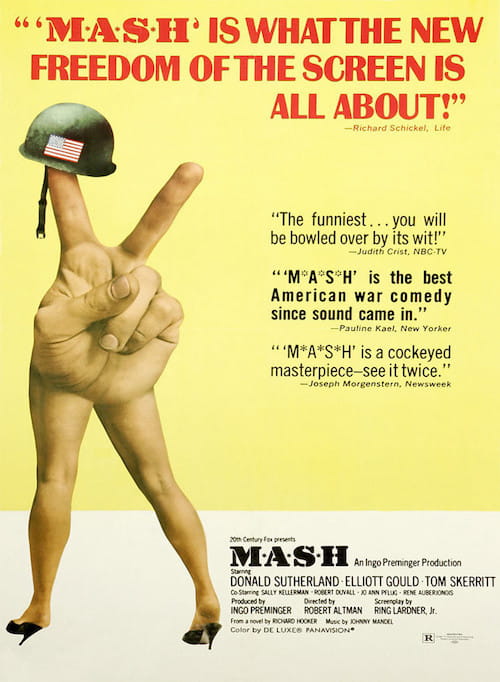

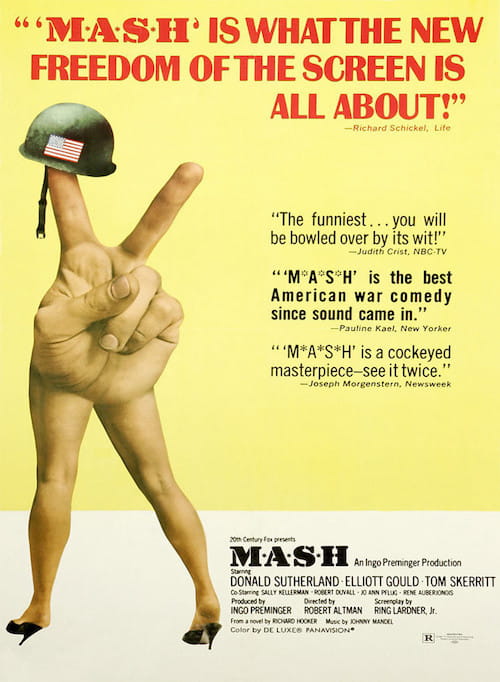

M.A.S.H.

Robert Altman

1969. Screened at Cannes, Easy

Rider

signalled the revolt of non-conformist youth and the first steps of a movement that

would soon become known as The New Hollywood. One year later, Robert Altman

denounced, in his own roundabout way, American intervention in Vietnam.

Dès sa sortie, M.A.S.H

was an immediate hit – so much so that it was adapted into a TV series broadcast from

1972 to 1983. The Jury of the 23rd edition awarded it the Grand Prix du

Festival (which replaced the Palme d’or between 1964 and 1974).

Source: Slash film

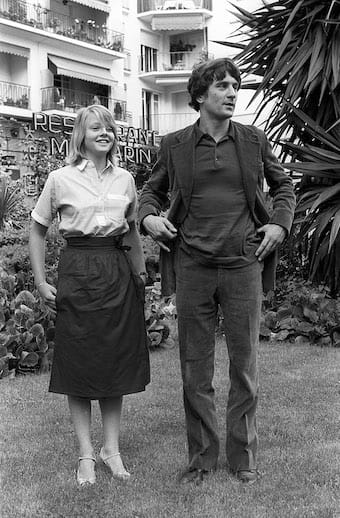

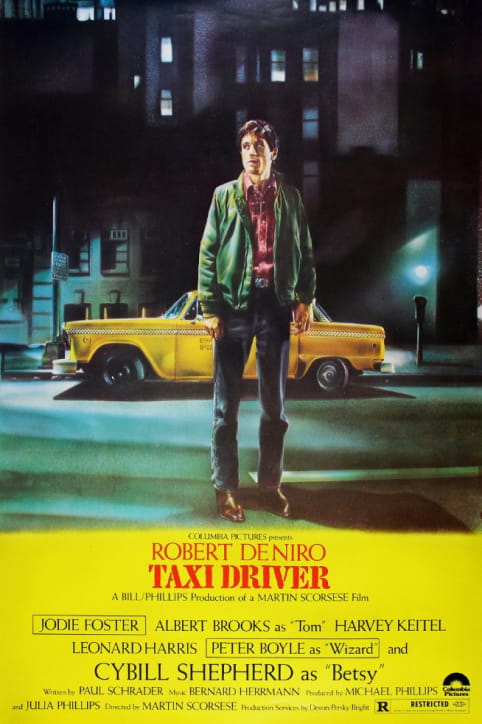

Taxi Driver

Martin Scorsese

New York as a backdrop, alienation and violence as the main themes: this mythical film

paints the picture of a taxi driver and his insomnia, the result of his probable past in

Vietnam.

Selected for the 26th edition of the Festival, Taxi

Driver was met with boos during its screening. In response,

Martin Scorsese, Robert de Niro and Harvey Keitel refused to meet the

press leaving 13-year-old Jodie Foster to handle the interviews. The Jury,

however, did not share the opinion of the journalists and awarded the Palme

d’or to the film.

Source: France Info

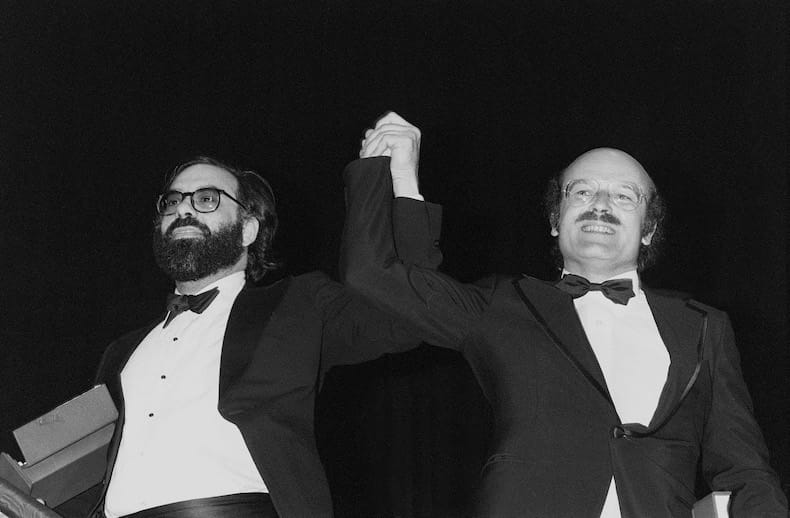

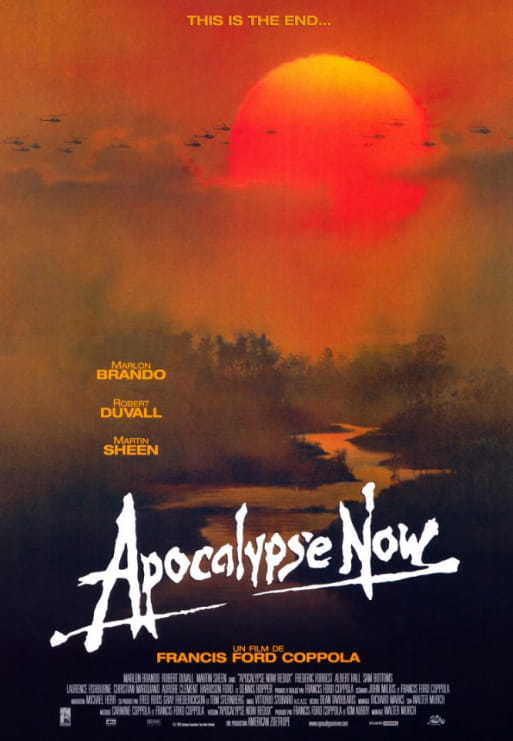

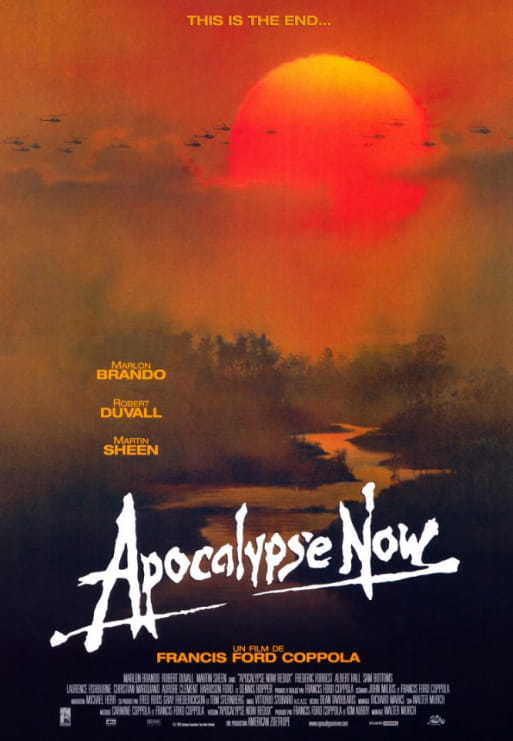

Apocalypse Now

Francis Ford Coppola

After a nightmarish shoot, Francis Ford Coppola presented his film as a work in progress, the first of its kind In Competition at Cannes. While Apocalypse Now was well received during its screening, there was a dissenting voice. Françoise Sagan, president of the Jury of this 32nd edition, hated the film and was not shy about saying so. Little matter, the Palme d’or was awarded to the American director, who tied with Volker Schlöndorff for The Tin Drum. A crowning achievement for Coppola, who had won his first Palme d’Or five years previously for The Conversation, making him the first director to win Cannes’ highest distinction twice..

Sources: Télérama, France Info

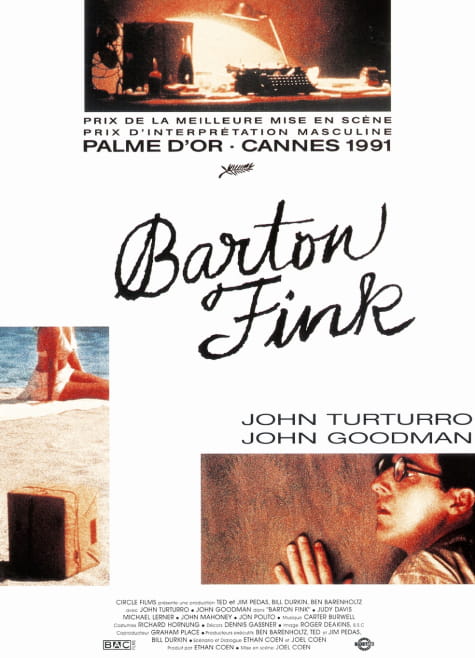

At the beginning of the 1990s, the Festival displayed a new ambition: to value films with an assertive aesthetic stance that were nonetheless capable of reaching a wide audience.

Barton Fink

Joel et Ethan Coen

The Coen brothers’ fourth film made off with everything. In Competition for the 44th edition of the Festival, Barton Fink took home the Best Actor Prize for John Turturro, as well as the Best Director Prize and, finally, the Palme d’or: a historic and unprecedented hat trick. As time would go on, only two other films would receive three awards. Bruno Drumont’s L’Humanité dand Michael Haneke’s La Pianiste, each winning the Grand Prix of the Jury and the Best Actor and Best Actress Awards.

Source: Sud Ouest

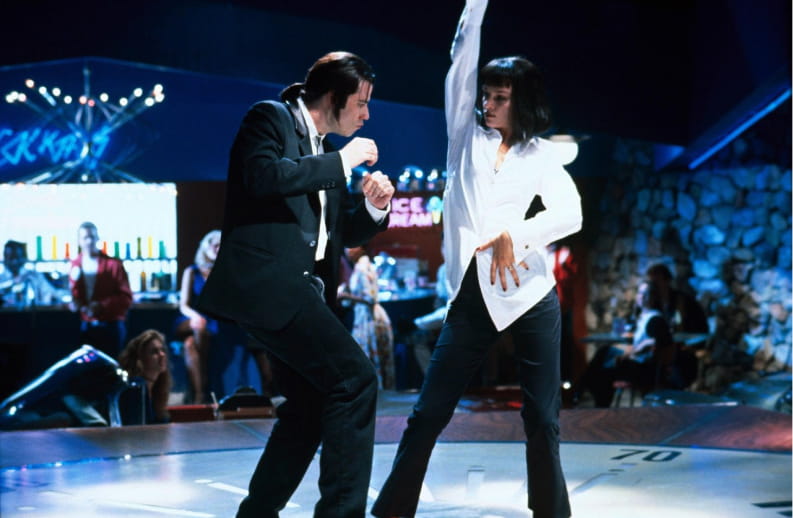

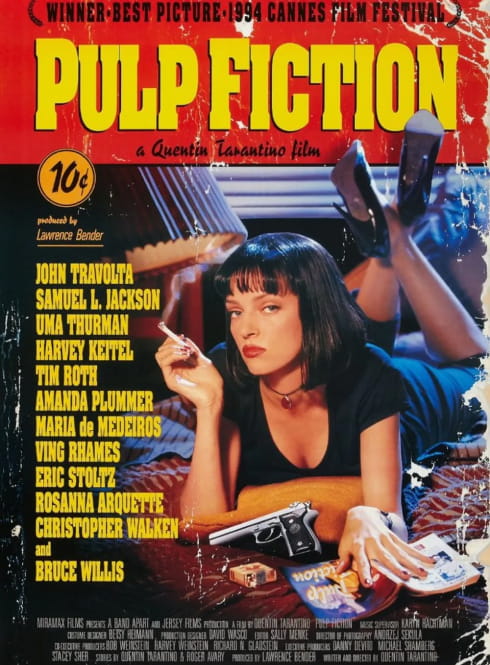

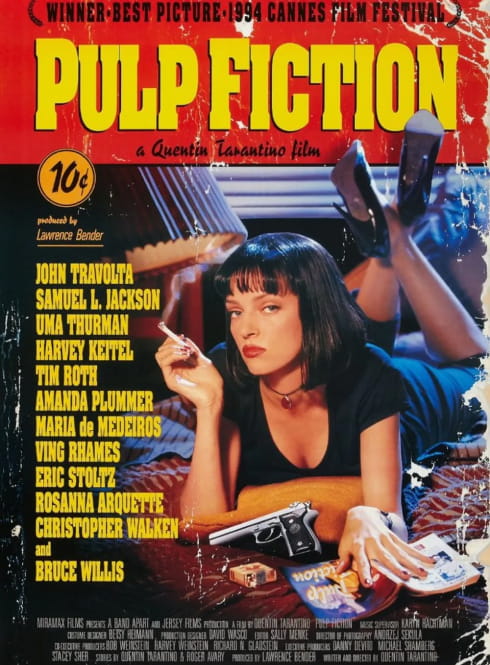

Pulp Fiction

Quentin Tarantino

After Reservoir

Dogs,

screened Out of Competition in 1992, Quentin Tarantino returned to the Croisette with a

second feature film, this one presented In Competition.

Despite a lukewarm

reception during its screening, he Jury, presided over by Clint Eastwood,

awarded it the Palme d’or, to widespread surprise. More than thirty years

after its release, Pulp

Fiction has become a cult film and remains an essential

aspect of contemporary cinema.

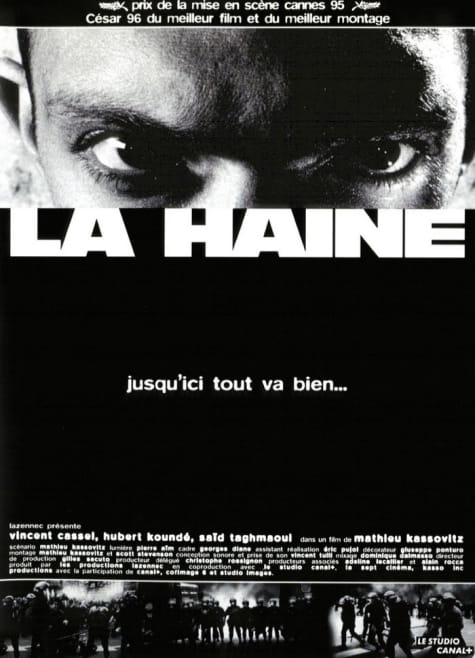

La Haine

Mathieu Kassovitz

Two syllables were on the lips of all the participants of the 48th edition of the

Festival. Arriving in numbers to promote the film, the team behind La Haine

quickly attracted love from the festival goers. But when they climbed the steps of the

Palais des Festivals, the police who were providing security turned their back on them

in protest against a film considered “anti-police”.

The following day, the Jury

awarded the Best Director Award to Mathieu Kassovitz. In France, the

film quickly became a social phenomenon, with more than two million

tickets bought.

Sources: France 3, Criterion, INA, Radio Canada, Box-office

And as far as Selections are concerned, this demanding search for innovation led to the arrival of a handful of Scandinavian directors, who, at the turn of the century, advocated for sobriety and austerity in their conception of cinema.

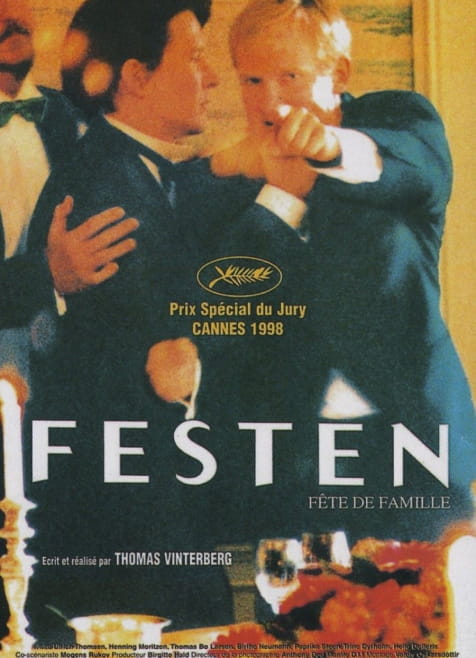

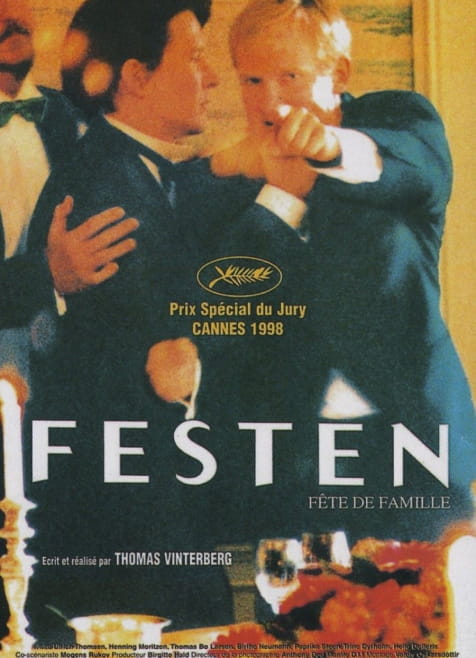

Festen

The Celebration

Thomas Vinterberg

Three years after the writing of the manifesto, the first film of

Dogme95

was selected In Competition during the 51st edition of the Festival. The Celebration

consecrated the “vow of chastity” demanded by the movement: no artificial light, filming

with a portable camera, no credit for the director. Only the use of 35 mm film was not

adhered to.

Doubtful of the success of his film, Thomas Vinterberg received an

ovation from the audience during the screening of his film at Cannes. The

Celebration won the Jury Prize and definitively launched the

career of its director.

Sources: France Culture, Télérama, Bande à part

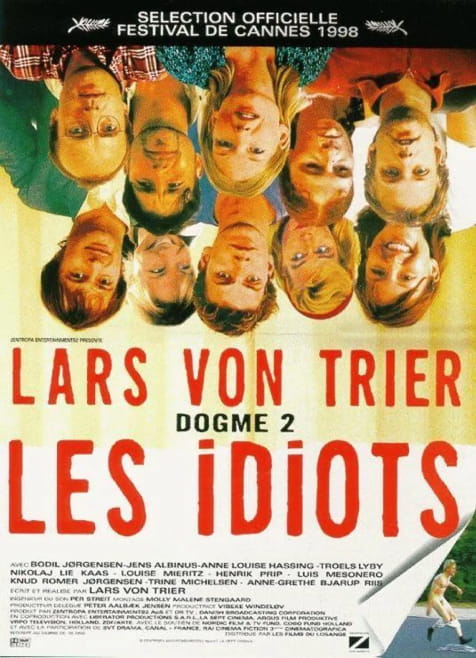

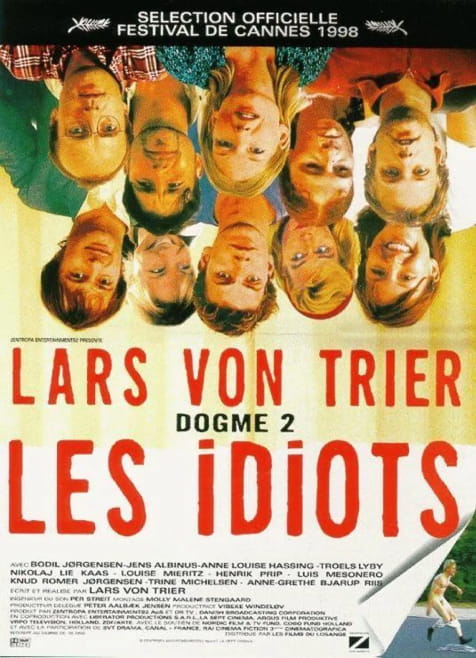

Idioterne

The Idiots

Lars von Trier

The same year as Festen, the Official Selection of the Festival picked Les

Idiots, the second film to be labelled as Dogme 95. This was not the

Danish director’s first rodeo at Cannes: he had already won the Jury Prize twice, for Europa and Breaking

the

Waves, as well as the Grand Prix de la Commission Supérieure Technique,

for The

Element of

Crime.

Highly anticipated and a favourite for the

Competition, the film won no awards.

That being said, it left nobody indifferent: a shocking subject,

violent directing, a part of the theatre applauded, the other hissed the director... who

did not attend the press conference, letting the team behind the film speak in his

stead.

Sources: Telegraph, L’Orient-Le-Jour

Dancer in the Dark

Lars von Trier

Inspired by the aesthetic developed by Dogme 95, Dancer in the Dark the third film of the “Golden Heart” trilogy, will mark the Danish director’s triumph at Cannes. Winner of the Palme d’or, this musical drama became the first feature film shot on digital camera to receive this highest distinction. As the main actress and composer of the score, Björk was granted the Best Actress Award.

Sources: Centre Pompidou, CNC

For several decades, films from Australia, China, Cuba, India, New Zealand and the Philippines have been part of the Official Selection. But at the beginning of the 21st century, it was to Southeast Asia that the focus turned.

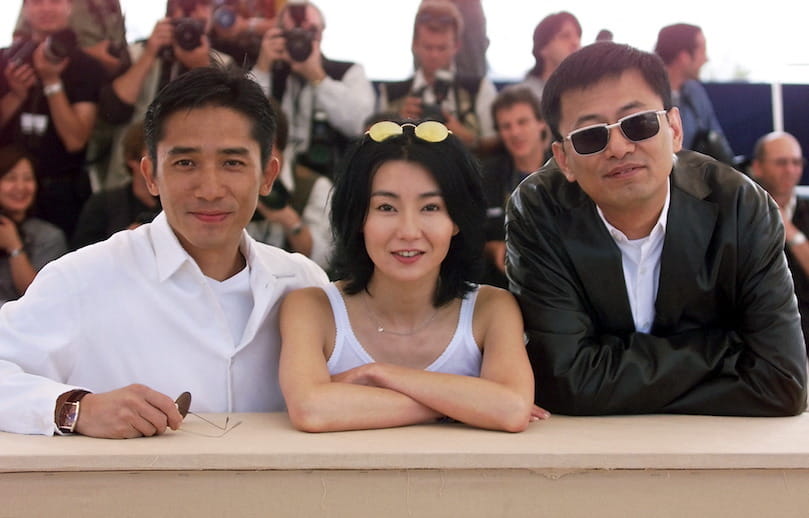

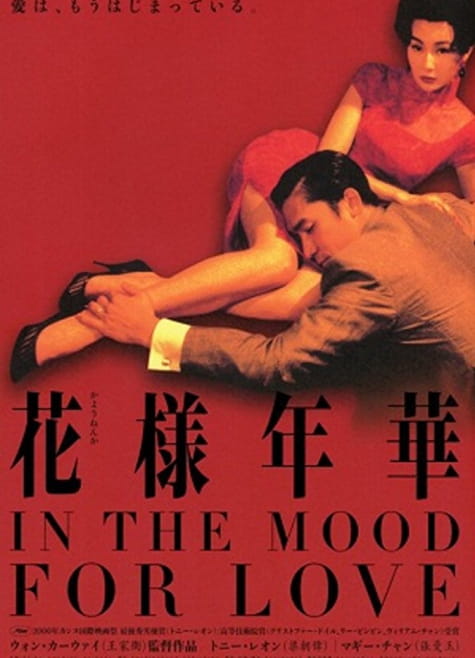

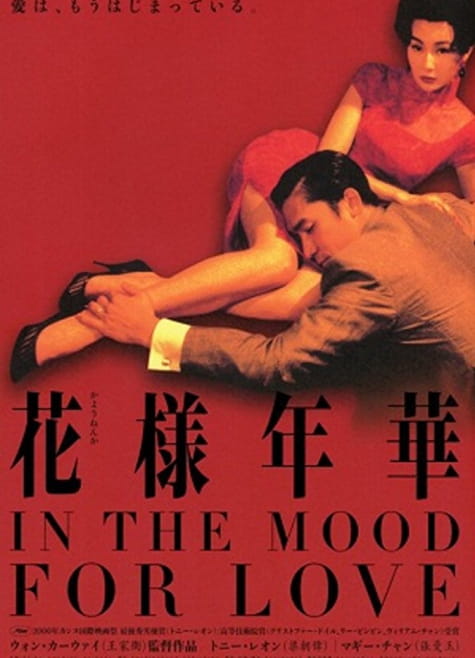

In the Mood for Love

Wong Kar-Wai

Time was running out, Cannes was coming up soon, and Wong Kar-Wai had yet to finish his

film! The Hong Kong director worked until the eleventh hour to provide a copy of the

film for the Competition.

Selected for the 53rd edition of the Festival, it took

home the Best Actor Award for Tony Leung Chiu-wai.

In

the

Mood for Love became a classic for film lovers. Ten years after its

release,

Xavier Dolan paid tribute to it in Les Amours Imaginaires -

Heartbeats, selected for Un Certain Regard in 2010.

Sources: Britannica, South China Morning Post, Ecran noir

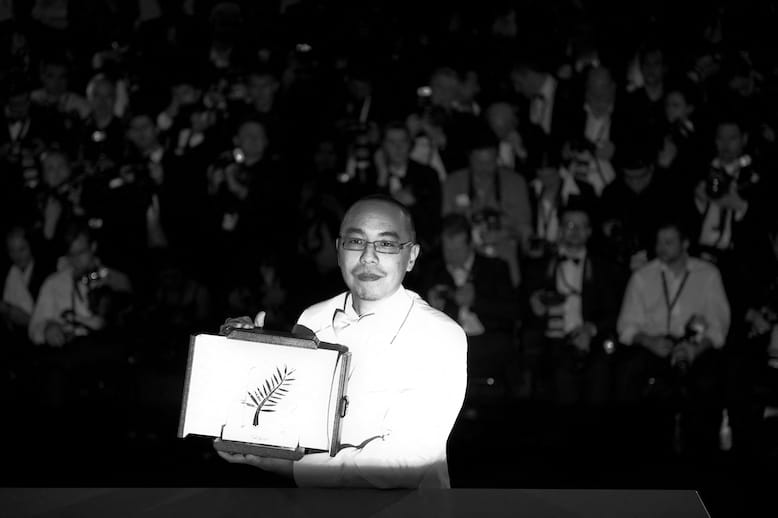

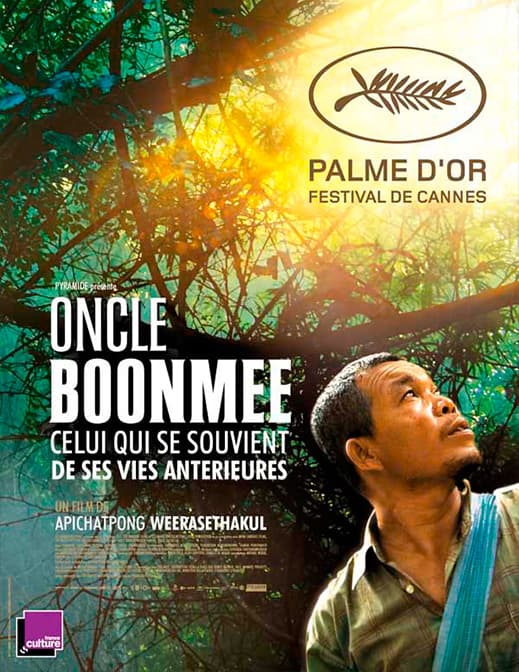

Lung Boonmee raluek chat

Uncle Boonmee, Who Can Recall His Past Lives

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

After two award-winning films (Blissfully Yours, winner of the Un Certain

Regard prize in 2002, and Tropical Malady, winner of the Jury Prize (tied) in

2004), the Thai director made his return to the Croisette with Uncle Boomee, Who Can Recall His Past

Lives, a new experimental feature film.

Several

days prior, it was uncertain if the director would be able to make it: with the

repression of the Red Shirts going on in Bangkok, the director went to the airport...

without his passport, left behind in the burning city centre. Going back to get it would

be too dangerous, so he was given a special passport to go to Cannes. A good thing, too:

Apichatpong Weerasethakul won the Palme d’or of the 63rd edition of the

Festival!

Sources: Le Point, Universalis, FDC, FDC, Critikat

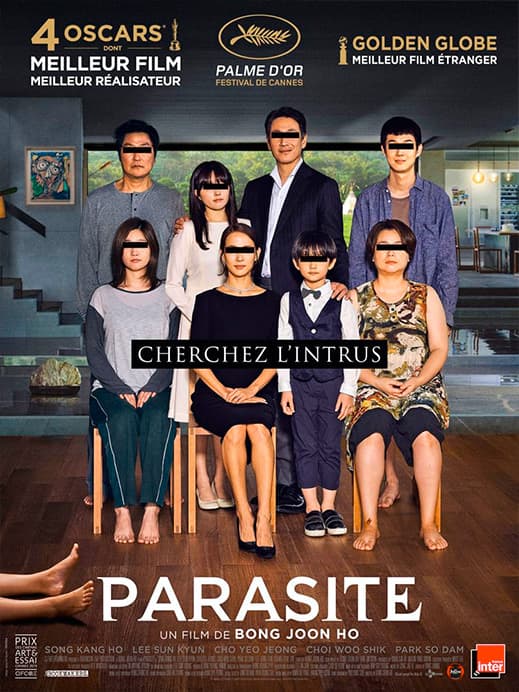

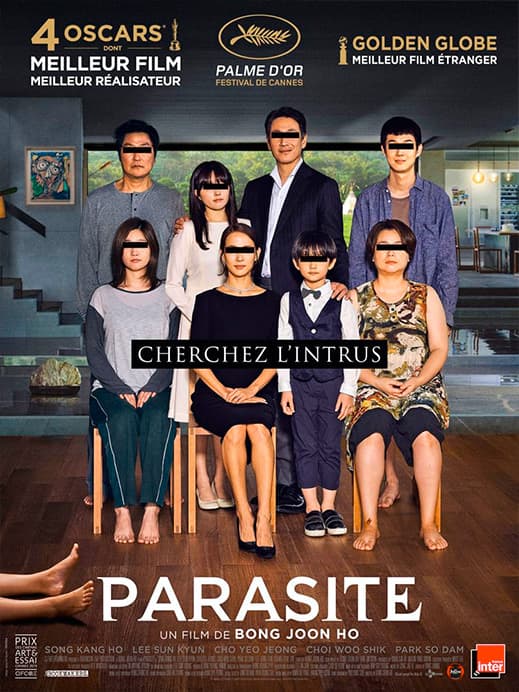

Gisaengchung

Parasite

Bong Joon-ho

While Korean films had already received awards (in particular Old Boy winner of the Grand Prix in 2004, and Thirst, winner of the Jury Prize (tied) in 2009, by Park Chan-wook) it wasn’t until 2019 that a Korean film took home the Palme d’or. Presided over by Alejandro González Iñárritu, the Jury of the 72nd edition unanimously awarded Bong Joon-ho’s social satire. This distinction confirms the durability of links that have been made between South Korea and the Festival since the 1980s. After its widespread critical success, Parasite was a box office hit and shone a light on demanding auteur filmmaking that could nonetheless reach a wide audience.

Sources: Boxofficepro, SensCritique, 20 Minutes

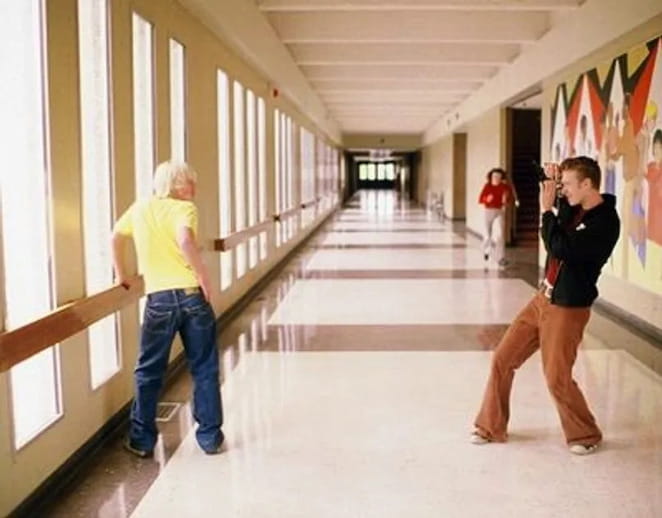

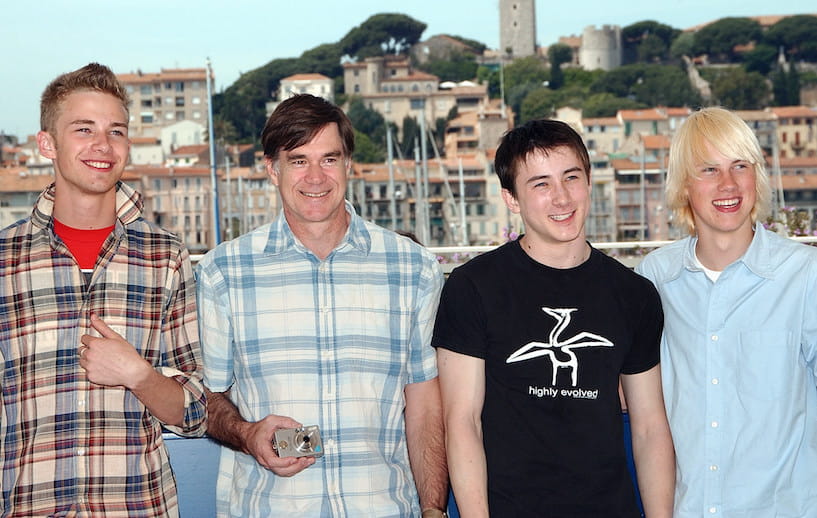

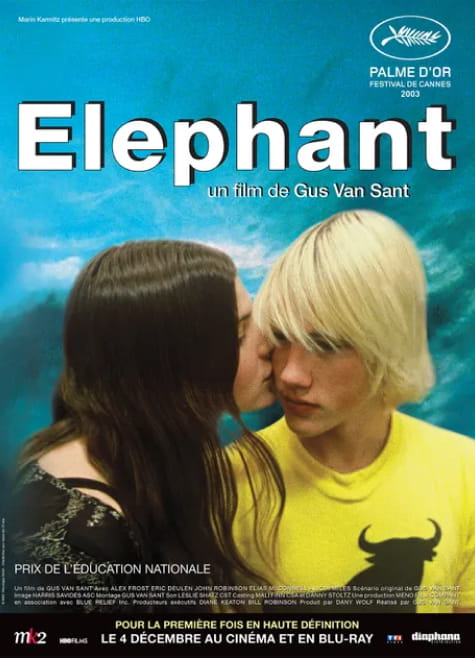

Elephant

Gus Van Sant

After his beginnings in independent cinema, then Hollywood productions, Gus Van Sant

took a step back from big-budget pictures. As can be seen in Elephant, his films took a new direction at the

beginning of the 2000s: more stripped down, they are also more demanding on a technical

level.

In 2003, his story inspired by the Columbine tragedy wone the Palme

d’or and the Best Director Award at the 56th edition of the Festival. A

remarkable performance: the first film to win two filmmaking awards since the Coen

brothers’ Barton Fink in 1991.

Sources: INA, Washington Post, Variety

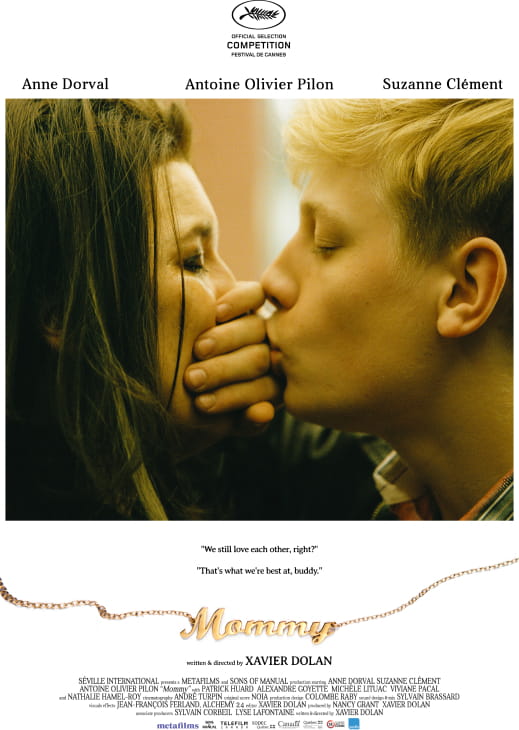

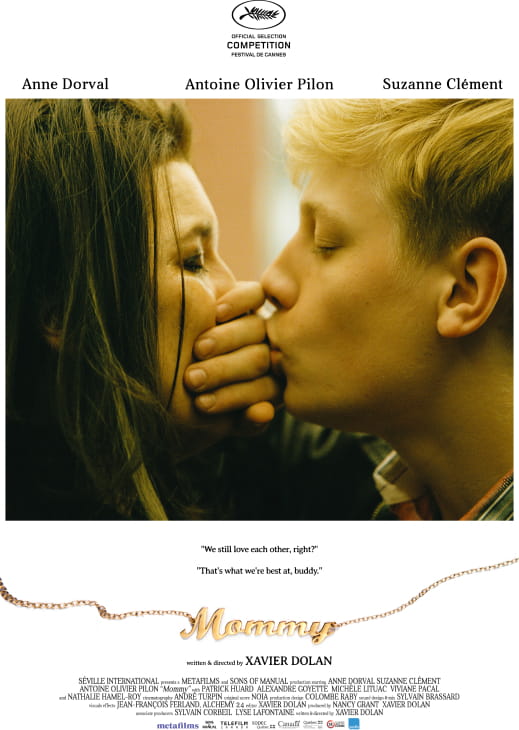

Mommy

Xavier Dolan

After award-winning debuts on the Croisette for Les Amours Imaginaires - Heartbeats

(Un Certain Regard 2010) and Laurence

Anyways (Best Actress Award (tied), Un Certain Regard 2014), the young

Quebecois entered into Competition with his fifth feature film.

In the running for

the Palme d’or, Mommy

ultimately won the Jury Prize, after having been a sensation throughout the

festival. Xavier Dolan took advantage of the award ceremony to thank Jane Campion (Palme

d’or (tied) for The Piano in 1993) and launched

an appeal to his generation: “In sum, I think that anything is possible to those who

dream, dare, work, and never give up. And this prize is the most radiant

proof.”

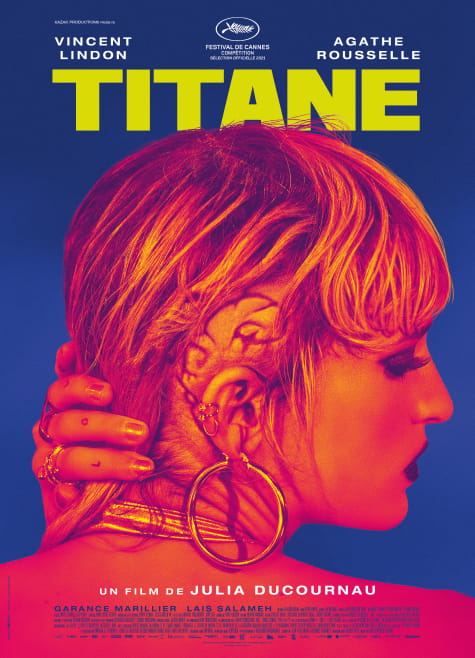

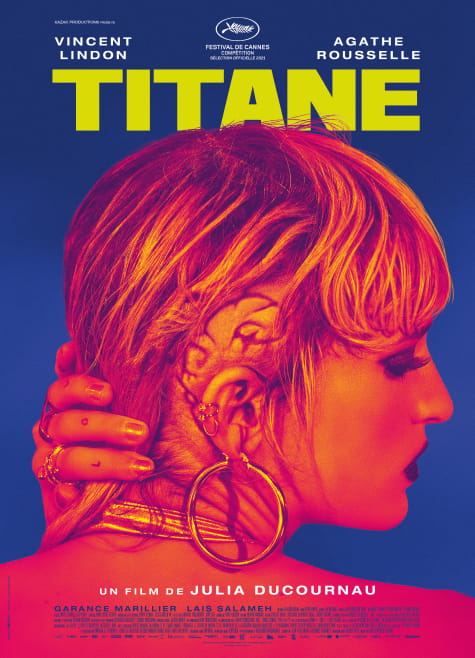

Titane

Julia Ducournau

After a year without awards in 2020, the 2021 edition marked the return of Competition

to the Croisette.

Already noticed with Grave - Raw (Semaine de la

critique 2016), Julia Ducournau returned to Cannes with Titane, her second feature film in her own

characteristic style. By using the

rules of genre filmmaking, the director deals above all with

mutation and interrogates our relationship to the body. By winning

the Palme d’or for this 74th edition, the French director became the second

woman to take home the highest honour, twenty-eight years after Jane Campion.